Bible translations at the edge of the world

What is it that doesn’t answer if you knock on the front door many times, but when you knock on the back door once, it quickly comes out the front door?

Along Jamir, translation director in the Bible Society of India, asks a riddle of the Nagas with a grin on his face. A steaming pot of the right answers, conch with shells, are brought to the table. They have been picked from watery rice fields in Nagaland, northeastern India. The shells are cooked with ginger, garlic and chili. Jamir shows the solution to the riddle, i.e. how to eat the conch: first you rummage through the back door, only then does the snail come out of its shell through the front door.

India is a huge country with many countries inside it. Each state has its own rich culture, food tradition, customs and languages. It tells a lot about the scale, that more than 1,700 languages are spoken in the country. “Right now, 110 Bible translation projects are active, most of them are located in northeastern India,” says Jamir, who himself is from Nagaland. “I have seen for myself, the word of God changes these communities when they have received the heart of the Bible in their language.”

One of these communities is the Chokris, who received their Bible in their own language last year. The town of Pfütsero is located in the Naga mountains at an altitude of 2133 meters and the locals call the place “the edge of the world“. The clouds hang evenly over the city, but when the visibility momentarily clears, you can see the lush mountain jungle and persimmons, tea and kiwi in the embankment plantations. Many people speak English, Nagamese or Hindi, but your own language and identity is important.

Dr. Along Jamir

Bible as a confirmation of language identity

Northeast India is a corner of a vast country that comprises of seven states. There are different ethnicities and languages in the area. The language base is not shared, so the nations do not understand each other. The region already has established Christian traditions and in three states, Meghalaya, Mizoram and Nagaland, Christianity is the main religion. Unlike in some parts of the country, Christians here do not face persecution or structural discrimination.

There are 95,000 native speakers of Chokri. Christianity arrived in Nagaland in the 1950s and Chokris are mostly second or third generation Christians. In the past, traditional religion prevailed in the region, where one believed in one greater God and the spirits of trees and forests. Just as the Finnish language got its literary form through Agricola’s translation of the New Testament, the Chokris also got a literary language with the translation of the Bible. “Many languages or entire language families have no writing form, letters, grammar or structure. In connection with the Bible translation, these are established,” explains Jamir, the director of the translation work.

Chokri is a spoken language and the people have a rich oral culture. Since there are many speakers of different languages living in the area, however, English and Angami are used as common languages. You cannot learn your mother tongue in schools. Young people have learned to read in other languages, including the Bible.

“We prayed the Chokri Bible for so long. Now we are happy when the Bible is in our hands. Before, the Bible felt like a foreigner, now it feels more personal.” Pastor Zo says. He organizes Bible reading gatherings in his congregation. “The Bible in the Chokri language is a matter of honor for our people and our language. There is little literature in the Chokri language other than the Bible. I would hope that this would start a process that would allow us to get a dictionary in our own language, school books and other literature.”

The transition from an oral culture to a written one has taken some getting used to. “At first, reading the Bible in Chokri felt strange, because before there was no possibility to read Chokri, I just spoke it. I read the Bible in English and Chokri side by side and that’s how I learned my own language. Now my vocabulary in my native language has grown! For example, salvation and justice are abstract words that I hadn´t heard before in my own language.” says Ruysuhli Cushah, director of youth work at Pfütsero Baptist Church. Pulalii Thelu, director of the Sunday school work in the same congregation, nods and continues: “The Bible in Chokri is a great achievement for our people. It is the starting point for creating something new and greater for the benefit of our people and for the glory of God.”

The Bible in one’s own language has also helped to understand the contents. “When you have the Bible in your own language, it becomes closer. The more we read it, the more we understand,” says Thelu.

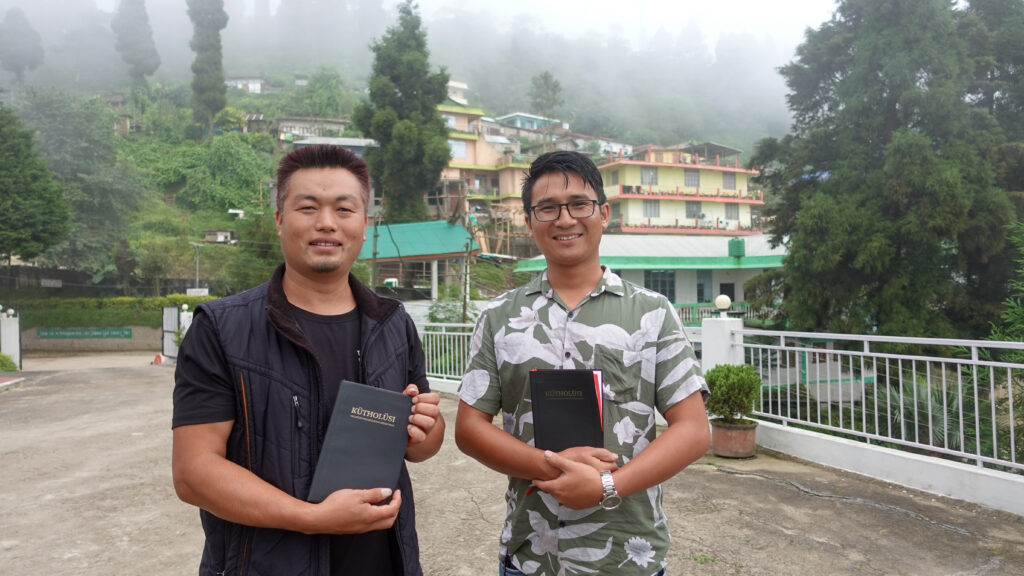

Mutukhro Zo and Thujosayi are happy to have the chokri Bible in their hands.

From skull hunters to Christians

It was the last moments of the rainy season in northeastern India. Bamboos and banana trees grow in lush clumps. Waterfalls cut through the jungle slope. The heavy rains have softened the roads into mud. In some places, the road has collapsed down the slope, and roads in the mountains have to be renewed every year. In the state of Arunachal Pradesh, at the tail of the Himalayan mountain range, a Bible translation into the Nokte language is expected. The New Testament has already been translated and the same translation team is currently continuing with the Old Testament.

The region has a long tradition of skull hunting. The last skull was cut off among this nation in the 1980s. The people follow the king system, which is also recognized by the Indian state. The current king is a Christian. The king’s eyes light up when he tells what the experience was like to read the newly completed New Testament in Nokte language. “Before the New Testament in Nokten, I translated it into Hindi and English. We thought Jesus was Hindi or English. Now we feel that Jesus is one of the angels and is speaking to us. We don’t have any other books to review yet. This is the way we can learn Nokte.” king Manwang Lowang tells. “The New Testament is a step towards preserving our language. I am happy that my daughter can now read Nokte!”

Translation is cooperation

The Bible Society of India emphasizes that Bible translations are always made for already existing churches and Christian communities. The Bible society is a handmaid for the local churches. Before the translation, a precise assessment of the need is made and discussions are held with the different churches and communities in the language area. Once the translation has been decided, a translation team is selected and they are trained in both translation principles and technical tools. Local native speakers of the language are acting as translators. “Bible translation should be meaning-based and culture-oriented. We do not translate word for word, but try to bring out the meaning of the phrase and make use of local sayings and expressions. We aim for a rich translation that is natural to read and faithful to the original text.” Jamir clarifies.

Bible societies leads translation projects and helps translators in their work. In addition, the translations have local testers and a steering group that includes representatives of local churches. The Bible society of Finland financially supports translation projects in northeastern India.

“We are grateful to all Finns who have supported Indian translation projects. They have a huge transformative power here. This is a challenging time for minorities in India, but we should remain strong and trust in God. Our God is greater than any challenge thrown before us.” Jamir assures.

Christianity grows despite the difficulties

India has freedom of religion, but converting is illegal. Under the current government, the position of Christians in India has become more difficult. During the last 10 years, the political situation has tightened in many parts of the country. In northeastern India, in the state of Manipur, there is an armed conflict between two different peoples, which is being followed closely throughout the rest of India, because the peoples are representatives of different religions.

In the capital, New Delhi, in “mainland India”, Christians live as a minority. The street scene of Delhi shows Hindu temples, small Hindu altars built on tree branches or on the pavement, green-yellow “Indian helicopters” or tuktuks, people in colorful clothes, and street advertisements proclaiming “one India”. For the Christian minority, one India would mean that, for example, funerals or weddings would have to be performed in Hindu ways and religious diversity would be put into one mold.

Hinduism is strongly supported by the state. Schools do not receive money from the state if there is no Hindi teacher, and the Hindi teacher’s salary is paid by the state. Every school must practice yoga, which is strongly considered a form of practicing Hinduism.

Catholic Church Archbishop Anil Joseph Thomas Couto represents Christianity in many interfaith negotiations and in relation to the government in India. “Christians are second-class citizens here,” Couto states unequivocally. “For example, getting a job or acquiring property is more difficult as a Christian. Christians are outside the law: their trials are regularly prolonged. In recent years, there has also been an increasing amount of harassment and attacks against Christians. Church services have been suspended.”

Although it is a journey from the capital to Manipur, the North Eastern state is on the Archbishop’s mind. “I consider the situation a warning to all Christians in India. If where Christianity has a strong place, it is possible to act like that, then the attack can happen anywhere else.” There are many Christians in Manipur. Bible translation projects in the area are currently on hold, as both translators and parishioners have had to flee their homes that have been set on fire.

Despite the difficulties, however, Christianity is growing in India. “People are looking for salvation, liberation and forgiveness. In Christianity, equality speaks to Indians, because Christianity does not support the caste system.” Couto ponders. The latest annual statistics of the United Bible societies tell about the growth: India was the world’s third largest country in the sale of Bibles with a sales figure of 2.5 million, and the Hindi Bible was the tenth best-selling Bible in the world.

Next year’s elections in 2024 are important. “We have hope and there are many good interfaith discussions. Within Hinduism there are many reform movements and educated Hindus who believe in equality.” Couto tells.